A granny summary of an article by Noa Handelsman and Dror Dotan

Reading numbers is hard, and the difficulty is a syntactic one:

A descriptive analysis of number-reading patterns in readers with and without dysnumeria

In a previous granny summary, we told you that reading multi-digit numbers is a difficult, multi-staged cognitive task. We also told you some people find it particularly hard, because they have dysnumeria.

Have you ever heard of dysnumeria before? You probably heard of dyscalculia, but it is not the same thing. Dyscalculia is an umbrella term for mathematical disorders – mainly in calculation, but some also use this term to indicate difficulty in estimating quantities or in other aspects of processing numbers. Dysnumeria is something much narrower – a learning disorder in reading or writing numbers. Unfortunately, dysnumeria is not as “famous” as dyscalculia. It is often under-assessed, or wrongfully assessed as dyscalculia. This means that even though dysnumeria could really impact everyday life (imagine, for instance, not being able to read your own bank account balance!), some people are unaware they have this disorder.

Precisely because of that, we think it is important to understand better how people read numbers and the origins of dysnumeria. In the present study, we asked two main questions: First, how many people struggle with reading numbers? Is dysnumeria a widespread learning disorder? Second, what are the common reasons for dysnumeria? Are there certain subtypes of dysnumeria that are more frequent than others?

We examined 118 typical readers, i.e., people who said they have no numbers-related learning disorders or difficulties in math. We had them do a task that seems trivial – read aloud 120 multi-digit numbers. Although the task seems easy, they erred in 6% of the items on average, which is not very low (for example, the error rates when reading words are typically lower).

We then asked how many of these people have dysnumeria. Based on several statistical criteria, we decided that making errors in 14% of the numbers or more is enough to indicate dysnumeria. Think about it this way: a participant had to err in at least 1 of every 7 numbers for us to determine dysnumeria. That’s a lot. We found that 7.5% of the participants (9 people) had dysnumeria. Recall that these are people who said they have no problem with reading numbers; still, they made errors in 1 of 7 numbers or more. Reading numbers is hard!

The next thing we wanted to know was why is number reading so hard. What is the most common reason for dysnumeria? To figure this out, we examined the types of errors our participants made when reading numbers. The idea is essentially very simple: reading numbers involves several different cognitive mechanisms, and each is responsible for a different aspect of the numbers. A momentary malfunction of one of these mechanisms would disrupt the processing of the specific aspect of the numbers of which that mechanism is responsible, and consequently we should observe a corresponding error pattern. For example, if the mechanism responsible for encoding the relative order of digits malfunctions, we should observe digit transposition errors – e.g., reading 1234 as 1243.

We classified the participants’ errors into 3 types, corresponding with the 3 main aspects of numbers:

- (1) Substitution errors – substituting one digit with another (e.g., 432 436).

- (2) Order errors – scrambling the relative order of the digits (432 423).

- (3) Syntactic errors – violating the number’s syntactic structure. For example, saying a number word that consists of the correct digit in an incorrect decimal class (ones, tens, teens, etc.) – e.g., 4302 4320 saying “twenty” instead of “two”. Another example for a syntactic error is decomposing the number, i.e., reading the digit string as few short numbers instead of as one whole number (432 forty-three, two).

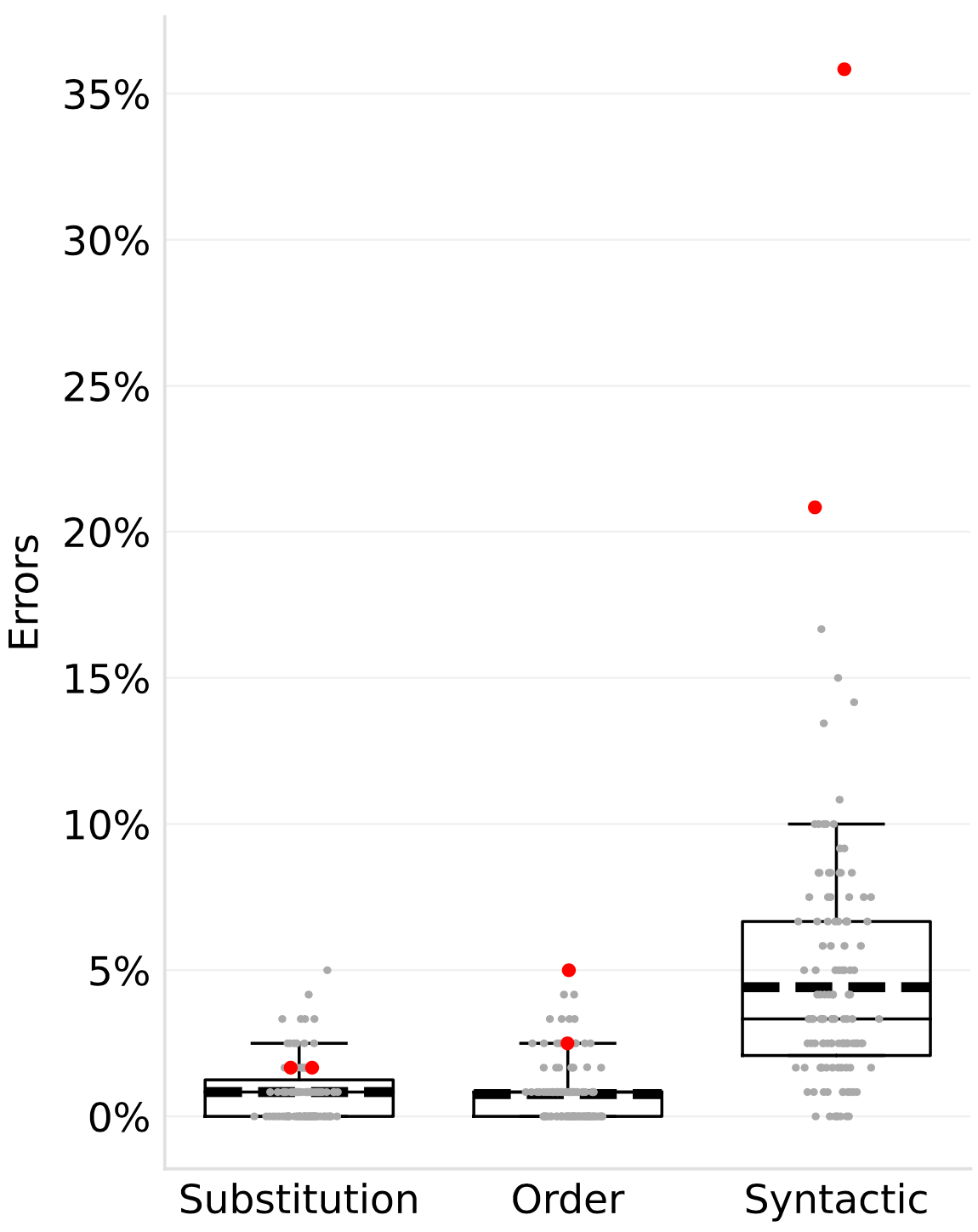

By far, the majority of the participants’ errors were of the syntactic type (see Figure 1). Namely, when reading numbers, the biggest challenge is to process the number’s syntactic structure.

Figure 1. The rate of errors of each type in typical readers. The thick dashed line is the average; the rectangle and the line in it show the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. Each dot is one participant (red=outliers).

This “syntactic challenge” was the story of the typical readers, those who do not have dysnumeria. Is syntax also the main reason for dysnumeria? To answer this, we examined 42 people who have dysnumeria (i.e., they had many errors in the number-reading task). They too made many more syntactic errors than substitution or order errors. Moreover, this trend was observed almost for each single individual. When we examined whether each of these 42 people has “syntactic dysnumeria” (a dysnumeria that disturbs the processing of the number’s syntactic structure), “digit-order dysnumeria”, or “digit-substitution dysnumeria”, all but one had a syntactic dysnumeria, yet only about half of them additionally had other dysnumeria types.

So, we are now able to say that dysnumeria is a relatively common disorder (7.5% of the population). Way too common to be as unfamiliar as it is. We can also see the main origin of difficulty in reading numbers, and the main reason for dysnumeria, is the need to process the syntactic structure of the number (we explain a little bit more about it in this granny summary).

How does all this translate into practice?

First, we think that awareness and proper assessment are the first step to effective treatment. So we created a dysnumeria diagnosis tool, called MAYIM. In parallel, we are trying to raise awareness to dysnumeria, especially among educators, teachers, and all those in charge of learning disorders assessment.

Second, as we now know that reading numbers, and that the origin of difficulty is the number syntax (also for children), we propose that schools should teach this skill explicitly. We have several activities in this direction.

Third, if you find yourself struggling with numbers, and you suspect you might have dysnumeria or dyscalculia; and if you are willing to participate in a research on this, we invite you to approach us. Maybe we can learn about your difficulty together.

Interested in more details? The full article is here.