A “granny summary” of the article by Dror Dotan and Naama Friedmann

A cognitive model for multidigit number reading: Inferences from individuals with selective impairments

What’s the trouble with reading numbers?

You’ll be surprised, but there are people for whom it’s a pretty big problem. There are people with a learning disorder in reading words (dyslexia), and there are those with a learning disorder in reading numbers. Dysnumeria is a learning disorder in reading or writing numbers (in contrast to dyscalculia, a somewhat vague term that some researchers use to denote a difficulty with calculation, and others use to denote a general difficulty with numbers).

What does it feel like to have dysnumeria? Take for example Chen, a woman I met during this research. She often used to get on bus number 24 instead of 42, because she would read the digits in incorrect order. When we examined Chen, we discovered that she confuses the order of digits when reading multi-digit numbers: e.g., she may see 4872 and read it out as 4782. She makes these errors not only when reading out loud, but also when she only needs to understand the number (like in the bus example): when I showed her number pairs that differed from each other in one digit, e.g., 2386-2346, she could easily tell they were different from each other. But if the two numbers differed from each other only in the order of digits, e.g., 2368-2386, she had 100% errors. Yes, it’s not a typo, 100% errors: she saw 36 number pairs that differed in the order of digits, and for each pair she stated that the two numbers were identical to each other.

Chen’s disorder manifests itself only when the numbers are presented to her in digits. She did very well in tasks in which the numbers were not presented as digit strings (e.g., she could easily repeat a number I said, or say out loud the answer to a calculation exercise). We concluded that Chen’s disorder is very specific: it affects only her ability to encode the order of digits in a visually-presented digit string. This conclusion is important because it teaches us not only about Chen. The existence of a disorder in very particular cognitive mechanism (the encoding of digit order) proves that this mechanism exists in the first place. That is, we can conclude that in the complex process of reading numbers, there is a specific process whose job is to encode the relative order of digits in a digit string. For most of us this process works fine, but for Chen it doesn’t.

By the way, Chen has a similar disorder in reading words – she confuses the order of letters. This disorder is called “letter position dyslexia”, and it is one of the most common dyslexias in Hebrew. Here you can see a piece of art, beautiful in my opinion, that Chen did as a student. She called it “Frustration”, and you can really see how all the letters from the keyboard get mixed with each other.

“Frustration” / Chen Zrahia

You may think “OK, so he discovered some sub-process in the number reading mechanism. How does this knowledge help us?” Well, the point is that Chen is not the only one with difficulties in number reading. There are many more people who find it difficult, and different people have different disorders. Some, like Chen, have a deficit in the mechanism that encodes the order of digits. Some have a deficit in another visual mechanism, which identifies the number length. Such is Tara (pseudonym): when she sees a number, say 4876, she is not sure how many digits it has, so she may read it like this: “Forty-eight thousand, seven hundred… hmm… sorry… four thousand eight hundred seventy-six” (when reaching the end of the number, she typically realises that she was wrong and corrects herself). Like Chen, Tara’s deficit is in the visual system, i.e., it affects number comprehension too, with no difficulty in saying numbers that are not presented visually.

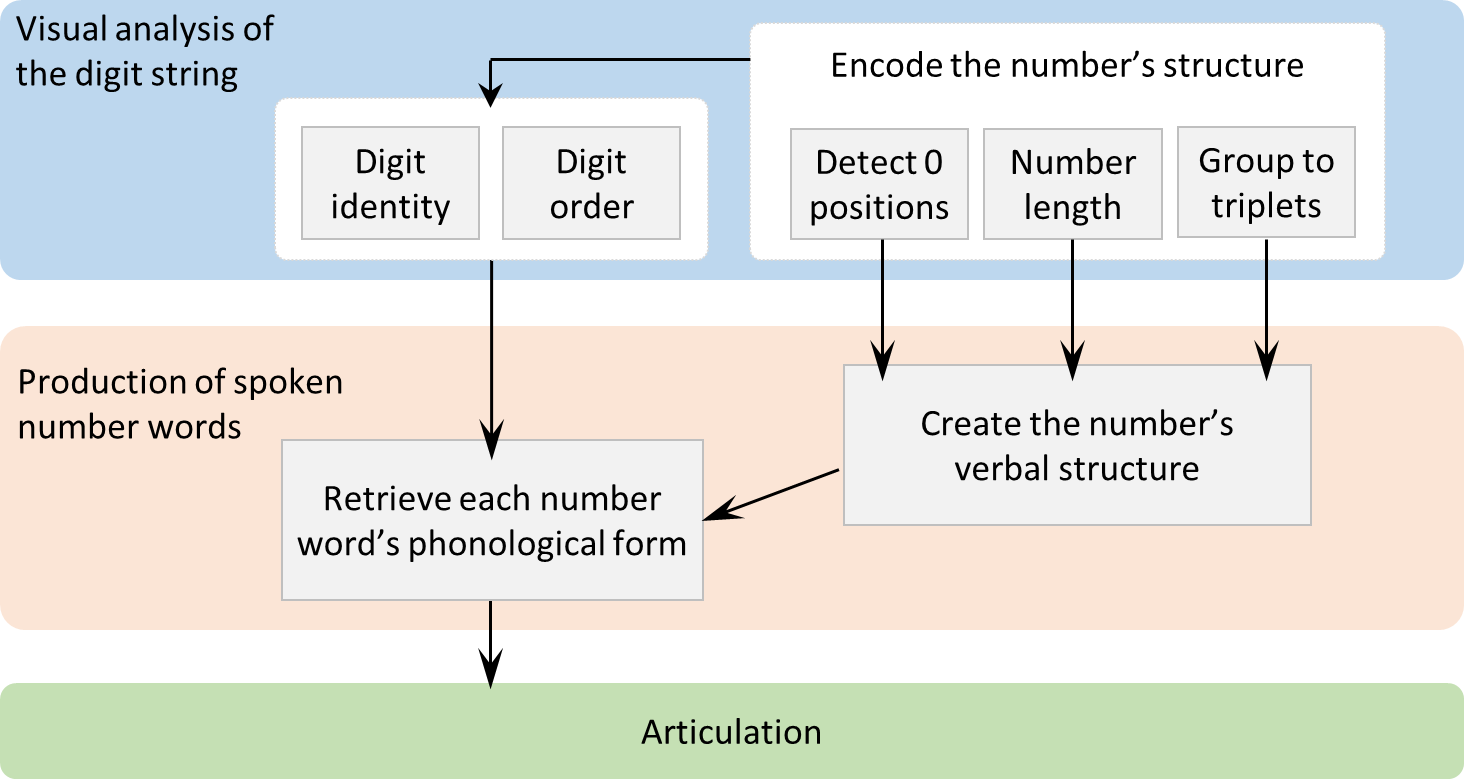

In our research we examined Chen, Tara, and 5 other people with number reading deficits. Each of them had a deficit a different number reading sub-process, so from each person we learned about a different part of the number reading process. By adding it all up together, we can understand how the number reading mechanism in the brain is built, end to end. The following diagram describes the structure of this mechanism.

Fig. 2. A cognitive model of reading numbers aloud

If you are interested in the details, read the text in green font: broadly speaking, when we read numbers aloud, a first set of processes (blue) analyzes the digit string, a second set of processes (orange) retrieves the corresponding number words, and a third process (green) articulates them. Each of these 3 processes consists of several components. In the blue part you can see, on second left, our old friend – the digit-order encoder, which is impaired in Chen. Next to it is a process that identifies each digit. To the right, there are processes that encode different aspects of the number’s syntactic structure: (1) How many digits it has (this is the process impaired in Tara). (2) The positions of zero. Encoding this information is useful because 0 is never pronounced, and our speech system probably wants to know as early as possible which digits will be pronounced. (3) Grouping the digits into triplets (e.g., 12345 is divided into 12 and 345). This grouping is useful because the next stage is saying “12 thousand and 345”.

The speech production stage also consists of several processes. The right processes generates the verbal number’s syntactic structure: e.g., it knows that for 73 you should say 2 words (tens + ones), for there is only one word in 100, even if it has more digits. What about more complex numbers, like 34,082? Well, if you really want to know, read the full article!

How does all this help us? In all sorts of ways. One is relevant to people with dysnumeria, like Chen. When the reading mechanism is so complex, it’s not enough to know she has dysnumeria (or “number reading disorder”), because there are many types of dysnumeria. A person can be impaired in any of the processes in the above mechanism; different types of deficits will cause different types of difficulties, and will require different types of different. By understanding the number reading mechanism, we can characterise the different types of dysnumeria, and develop tools to diagnose each type of dysnumeria and to treat it.

How many people are there like Chen and her friends? I don’t know of any thorough study that examined this, so I can only answer with an example. When I posted on facebook that I am looking for people without learning disorders for a research on numbers (as control subjects), many people reached out to me, mostly students, and all of them said they had no learning disorders. In fact, about 10% had some sort of number reading difficulty. Yes, my friends, as always we reach the same conclusion: numbers are difficult.

Interested in more details? The full article is here.